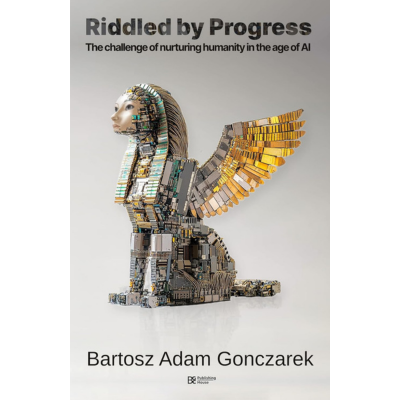

In this episode of Inside Personal Growth, host Greg Voisen welcomes Dr. Bartosz Adam Gonczarek, author of Riddled by Progress: The Challenge of Nurturing Humanity in the Age of AI, for a thoughtful and wide-ranging conversation about technology, meaning, and what it truly means to be human in an age increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence.

In this episode of Inside Personal Growth, host Greg Voisen welcomes Dr. Bartosz Adam Gonczarek, author of Riddled by Progress: The Challenge of Nurturing Humanity in the Age of AI, for a thoughtful and wide-ranging conversation about technology, meaning, and what it truly means to be human in an age increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence.

Rather than approaching AI as something to fear or blindly celebrate, this discussion explores a deeper question: Are we gaining answers while losing wisdom?

The Digital Sphinx and the Riddle of Progress

Early in the conversation, Dr. Gonczarek introduces a powerful metaphor drawn from Greek mythology—the Sphinx.

In ancient myths, the Sphinx posed riddles to travelers. Those who failed to answer were destroyed. In Riddled by Progress, Dr. Gonczarek suggests that today we face a modern version of that challenge: a digital Sphinx in the form of AI and technological progress.

The danger, he explains, isn’t that machines will take over, but that we may accept answers without understanding them. Like Oedipus, who solved the riddle but failed to grasp its deeper meaning, humanity risks mistaking correctness for wisdom.

AI can provide instant responses, generate text, and optimize decisions—but it cannot supply meaning. That responsibility still belongs to us.

When Answers Come Too Easily

Midway through the episode, the conversation turns toward a subtle but critical issue: over-reliance on AI-generated answers.

Dr. Gonczarek explains that the process of struggling with questions is essential to human growth. Meaning is not transferred—it is created through effort, reflection, and lived experience. When answers are handed to us without engagement, we risk weakening our confidence in our own judgment and capabilities.

This loss of confidence, he argues, can quietly become a self-fulfilling prophecy—one where humans gradually step back from thinking deeply, believing technology will always do it better.

The Promethean Lag: Falling Behind Our Own Creations

Another key theme discussed is the Promethean Lag, a concept describing the widening gap between what humans create and what they can fully comprehend.

AI systems are advancing rapidly, yet most people interact with them without understanding how they work or what their long-term implications may be. Dr. Gonczarek stresses that this gap is not a reason to reject technology—but a reason to engage with it more thoughtfully.

Understanding, curiosity, and education must evolve alongside innovation, or humanity risks misusing the very tools meant to empower it.

Human Flourishing, Not Replacement

Despite the philosophical depth of the conversation, the tone remains grounded and hopeful.

As the founder of Vstorm, an AI consultancy working with organizations across Europe and the United States, Dr. Gonczarek brings real-world experience into the discussion. He emphasizes that well-designed AI systems can remove repetitive, mundane tasks and allow people to focus on creativity, judgment, and meaningful human connection.

When applied responsibly, technology can support human flourishing, not diminish it.

Reclaiming Meaning in a Technological World

Toward the end of the episode, the conversation shifts inward—away from screens and systems, and toward the inner world of human experience.

Dr. Gonczarek reflects on how some of the most important dimensions of life—meaning, depth, and authenticity—cannot be digitized. They emerge from presence, reflection, and conscious engagement with the world around us.

The real challenge, he suggests, is not solving the riddle faster—but learning how to ask better questions.

Final Reflections

Riddled by Progress is not a warning against technology. It is an invitation—to slow down, reflect, and remain fully human while navigating an AI-driven world.

As Greg Voisen highlights throughout the conversation, this episode encourages listeners to rethink progress itself and consider how technology can elevate—not replace—human wisdom.

Guest Links & Resources

Our Guest: Dr. Bartosz Adam Gonczarek

➥ Book: Riddled by Progress: The Challenge of Nurturing Humanity in the Age of AI

➥ Book Website: https://www.riddledbyprogress.com/

➥ AI Consultancy: https://vstorm.co/

You may also refer to the transcripts below for the full transcription (not edited) of the interview.

[00:00.2]

We're refacing the Sphinx, the reincarnated version of the Sphinx, the digital Sphinx. And if we don't know the answer, how to answer the riddle of progress, we might be destroyed. The real danger isn't robots taking over, but rather that they trigger in a steel net of disbelief in ourselves.

[00:23.4]

Maybe we should reconsider why, what the technology can do, instead of creating this doubt in us, set us to a new dimension or new heights. New heights, I think. New heights of consciousness. So he was able to conquer these things.

[00:40.6]

However, and it's a similar situation like with ChatGPT. You can, for example, apply for a job and have answers during the recruitment process handed over to you by ChatGPT, and you can land the job. The same happened with King Oedipus.

[00:56.6]

He conquered these things, but it led him to his doom, to his demise. Because he never understood what those answers meant. Welcome to Inside Personal Growth podcast. Deep dive with us as we unlock the secrets to personal development, empowering you to thrive.

[01:17.9]

Here, growth isn't just a goal, it's a journey. Tune in, transform, and take your life to the next level by listening to just one of our podcasts. Hi, this is Greg Voisin. I'm the host of Inside Personal Growth. I've been hosting this podcast show for almost, 19 years, 18 and a half years with over 12, 70 podcasts, from authors that are talking about, business and personal growth, wellness and spirituality.

[01:47.4]

And today we have a special guest. He's sitting across from you here in the studio, he in San Diego at Ignite bbb and it's Bartosz Gonczarek. Bart, good day to you. Great to be here. Thank you for inviting me. But Greg, I must tell you this is a special occasion to me because we know each other for years.

[02:06.2]

I'm a listener to your podcast. Being here in person is just fantastic. Well, I appreciate that. And for the listeners, here's a copy of the book. These are fresh off the press. He flew in from Poland. And these are the books that you will get at Amazon.

[02:21.5]

And we'll have a link in the show notes below. So look down below, to the website. And the book is called Riddled by Progress. But I think Bart Gottrick, it's probably a good idea he actually has a doctorate. So it's Dr.

[02:37.4]

Bart Gottrick. I want to tell the listeners a tad bit about you because I think that it gives them a perspective, and a context, for why somebody like you would actually, write a book like this.

[02:53.7]

So art he's a rare kind of renaissance figure in what I saw today's tech world. He's a successful tech entrepreneur, turned humanist philosopher who brings a uniquely informed perspective on the intersection of technology, humanity and personal growth.

[03:11.9]

He has a PhD in economics and degrees in mathematics, computer science and economics. And Bark co founded a company, which is where our relationship started. Called Explain Everything. It was an innovative interactive whiteboard platform that had transformed education for over 2 million students and teachers worldwide.

[03:32.4]

The company raised about 2 million in a series A funding and it was eventually acquired by Promethean. And then Bart was able to stay for another year and he's out now doing some very exciting things that we'll be talking about later.

[03:47.5]

So his journey took a profound turn. After decades of living through the highs and lows of startup life, from his early days as a hacker consultant on board of directors across Europe and building global tech company, he began questioning what we're losing in our relentless pursuit of technology.

[04:07.6]

It was interesting. Last night the guy from Nvidia, the interviewer asked him, said, AI, what are you supposed to do? And he said, well yeah, it's not going to get rid of Jobs if you know how to use it. So it was kind of like his way of answering, well, there's this whole fallout in the job arena that we're seeing right now, and that's current.

[04:32.2]

We just saw Amazon layoff 14,000, UPS lay off 39,000. But this book, riddled by progress, is really going to give the listeners an idea about what your thinking is and somebody who's so involved in AI as well.

[04:49.8]

And so Bart, let's just start this off. You've had a crazy journey from a teenage hacker, to writing operating systems and guides, and during early Internet days founding this Apple Award winning software company and now running an AI consultancy, called Vstorm V Storm S T O R For any of you out there, we'll put a link below as well to vstorm.

[05:23.0]

What was a pivotal moment for you that made you realize that you needed to stop and write a philosophical book about technology rather than just building it? Because I get a lot of people today, like I had a guy on yesterday, he goes, man, we got to go analog.

[05:40.7]

And I'm creating gains, meaning, board games. Right. And he was high tech and we see a lot of this analog stuff and we see a lot of this competition from the digital side and now obviously the runaway with AI.

[05:57.1]

So where was the moment for you? You decided, I'm going to write this philosophical book. But that wasn't stopping Greg. I mean, you can think of me as a possessed because I'm doing so many things at the same time. Some, some say that you know, there are individuals that can cram several lifetimes into one.

[06:15.3]

And it's kind of what, what is happening with me is that I feel that I need to provide something, create something of, of meaning, meaningful. And this keeps me going to work over hours, work on the book in the morning, work in the afternoon on the companies that I found and create.

[06:37.9]

So it's kind of running in the parallel. But you see, I'm one of the tech entrepreneurs, as you said. I've built company that was very successful in the us. I sold it, I'm building another one which is now currently very successful. But that's that's a tech element of my life.

[06:56.7]

Building companies, guiding people, getting things done. But there's also this intellectual component to it that I felt was missing if I would not, let's say, dive deep into those thoughts that I share in the.

[07:14.7]

So it's kind of like intellectual journey that happened along the way. And look, the inspiration for that came with a revelation that okay, I have a Ph.D. and I have, I've learned so many things, yet I'm not certain if I know enough about technologies that we use, for example, for AI.

[07:35.1]

So I ask myself, and myself, am I, am I authentic calling myself tech entrepreneur if I don't know the roots of it, you know, of the technology that we use. And this pursuit, propelled me to look deep and I went all the way down to the Greek myths to write this book through German philosophy, you know, what have you.

[08:00.8]

That's the Sphinx. Sphinx on the front of that I can explain why it's the Sphinx and anything else, but it was kind of a curiosity thing, you see. Well, look, in the preface to this book you mentioned that you would have written this book even if you sold only one copy to yourself.

[08:23.2]

That's true, yes. So look for all of you, he doesn't want to do that. He would like for you to read this book. So again, look to the link below and hopefully you'll go get a copy. But that's a striking statement in really kind of a metropolitan metric obsessed world.

[08:41.8]

Can you talk about what drove you to protect this work from market forces and what it costs you to do so? Sure. So imagine me going through source material and there's a lot of old books and a lot of New books.

[08:58.7]

And I see a difference between books wrote in the past and the current books that are published, these days, let's say, on AI And I see a pattern in all of those new books. They are made as a product, something to sell, I think.

[09:14.8]

I'm not, speaking about all the books, but in general, books become products, commodity. And I see that they are very similar. And I'm looking for depth in those books. And if you're exposed to a lot of material about AI you kind of see that they repeat the same pattern, the same set of thoughts.

[09:35.3]

And I got bored with that, to be honest. So I decided not to do this to my work. And instead of thinking of it as a product to be sold, to be easily digestible, a page turner. I thought of it. Okay. I want it to satisfy my curiosity.

[09:53.1]

I want it to be rich with ideas, full of them. Right. Even if it's going to confuse, people at first. Because it is challenging to dive deep into this rabbit hole that I have here. Right? It is, but it was meant to be challenging.

[10:10.0]

Then again, we're challenged by the progress ourselves. And the technologies that surround us are not simple. So I cannot use only lay terms to explain this complex puzzle of our world. So I had to dive deeper and bring the important thoughts and puts them into the book.

[10:30.4]

Well, so look, you did a lot of traveling physically to go to places where you could reflect. And you went to Delphi. You went to. Hopefully I pronounce this right. Witten Gatz. Wittengotstein. Wittgensteins.

[10:45.6]

Witts. It's a hideaway in the Norwegian fjords. Yes. Yes. Which I've never been to. So now I gotta go to it because I can't even pronounce the name. The place is called Schulze Jordan. Yes. Wittkerstein had his hideaway there. Yes. Okay. And other places of intellectual significance while writing this book.

[11:07.5]

So why was it important to be in these physical locations rather than simply reading about them? And what did the journey teach you that the books couldn't?

[11:23.6]

Great question. And thank you for asking, because this is really important. One of the reasons I decided to engage so deeply into this endeavor and be present in those places, visit them, try to understand the vibe there, and look for traces of those philosophers, poets and other thinkers was that I wanted this work to be authentic.

[11:47.7]

Look, we're surrounded with generated material, and it's really easy to generate text. These dense letters that is going to be, like, you know, grammatically correct, engaging, but it's not going to be authentic. I'm here authentically as a human being pursuing an idea, which is important part it is speaking about the future of ours.

[12:11.3]

So I'm pursuing, it's kind of like a challenge that I have in front of me. I don't want to cheat when pursuing this idea and making. Providing some solutions to face this challenge and generate it with some, I don't know, chatgpt, what have you.

[12:29.7]

Right. So it was super important for me to also be responsible for those ideas. I might be wrong with something. I'm a human being, of course, but those mistakes are mine. It's not something that I generated and something messed up along the way.

[12:47.2]

All of what you see here is a result of my genuine pursuit that I just wanted to get right. Well, let's talk about this Sphinx. We mentioned her. I'm going to hold the book up again. It's a core thesis.

[13:05.5]

It obviously serves as the central metaphor. Throughout the book, simultaneously, this monstrous and magnificent, threatening and inspiring Sphinx. Right? Yes. So in Greek mythology, the Sphinx devoured those who couldn't answer her riddle.

[13:24.9]

Yes. This book is called Riddle by Progress. Exactly. Okay, how is AI poised as a similar existential riddle to humanity today? And what happens if we fail to answer it?

[13:46.2]

That's a deep question. Let me answer first, why it's the Sphinx? And then later, what's the challenge ahead? I decided to create a story, a storyline that is kind of relatable because, look, we're dealing with technologies that are more and more abstract things, becoming less physical.

[14:08.9]

There's somewhere else. Like music. In the past, you had a record going like a viral, for example, you could change it with yours. And now you have some playlists on Spotify. It's more and more abstract. The same with, you know, thoughts, the concepts, all of that just kind of evaporates.

[14:26.6]

So it's not relatable. And in the past, people had physical things, you know, that they can manipulate, that were part of the world. Like today here, we're recording on two iPhones. But the audio files going into this computer.

[14:43.4]

I used to have recorders. Right. I still use them. I love physical media. And we're not talking about digital recorders. I'm talking about ones that you put cassettes in temperature. Yeah, I love those. But the thing is that, you know, you can lose your vinyl, for example, but it's yours, it's not going to evaporate.

[15:02.9]

What about your Spotify list? I don't know. If you lose your subscription or access to your account, it's gone. It's just too, it's, it's getting more and more abstract. That's a point. So what I was looking for is to give a progress, which is very abstract and multi dimensional, a face.

[15:20.4]

Right. And I was looking for something that kind of challenges you and can, as you mentioned, destroy you. That was the Greek Sphinx in the past in the smith of King Oedipus.

[15:37.8]

Smith was asking travelers, riddles and if they didn't know the answer, they got destroyed. Right. And to us it may be the same situation where we're facing the Sphinx, the reincarnated version of the Sphinx, the digital Sphinx.

[15:58.4]

And if we don't know the answer, how to answer the riddle of progress, we might be destroyed. The thing is that in this Greek myth, King Oediplus had his answers. The answers were given to him, so he was able to conquer the Sphinx.

[16:16.5]

However, and it's a similar situation like with ChatGPT. You can for example, apply for a job and have answers during the recruitment process handed over to you by ChatGPT and you can land the job. The same happened with King Olympus.

[16:32.5]

He conquered the Sphinx, but it led him to his doom, to his demise. Because he never understood what those answers meant, he couldn't apply meaning for them. So there was no wisdom, there was action, there was answers, they were correct, riddle was solved, Sphinx disappeared and he thought he's going to be victorious, but it actually killed him.

[16:57.5]

Isn't that the similar situation we're facing now? I would say exactly. It's like a mirror. It's a mirror of what we're facing now. You argue in the book that the real danger isn't robots taking over, but rather that they trigger in a steel net of disbelief in ourselves.

[17:20.7]

Can you unpack this also? How does your own loss of confidence in human capability become a self fulfilling prophecy? Great question. The steel net that is like creating a ceiling for what we can do is something that we create ourselves.

[17:44.0]

And it's something that I took from German poet and I'll give you the story, I opened the book with that story. The story's 200 years old and it's about a puppet dance. So you can imagine mannequin on strings and you have a professional dancer in that story watching the movement of that puppet saying oh, for the dancer this is game over.

[18:08.6]

Because we cannot move so graciously, so, so fluently through the dance floor because we need to defy gravity, right? And we need to pretend that it's so easy to move so great, but it's not, because, well, we're humans, right?

[18:29.3]

And this puppet, the fly that blows through gravity, and it's just better than us. And he thought to him, to himself, that was his first thought. Game over, right? And then he realized that if we think of those perfect dancers, those artificial dancers we would call them today, their achievements create kind of this belief in our own, possibilities, is that we will never believe that we can achieve something similar, because sometimes we can't.

[18:59.6]

And. And this creates this. This. This ceiling to what we can achieve is that we start to withdraw, saying, oh, there's this artificial thing that is better than me, right? And you start to withdraw, and you don't pursue excellence that way because you start to doubt your own possibilities, your own possibilities of achievement.

[19:22.0]

So that was the point that I took from that very old story, funny enough, and I won't give that away. But this author came to a very different conclusion at the end of that story, which sets the ground for the rest of the book, is that we think that we are limited by technology and the technology is going to replace us in some, domains.

[19:45.5]

Yet he saw that as a road forward. And I love that thought because it's so fresh. Despite coming from two centuries back, it's so fresh that we're still not getting it. So my point was that maybe we should reconsider what the technology can do instead of creating this doubt in us, Set us to a new dimension or, new heights.

[20:11.6]

New heights, I think. New heights of consciousness. I believe that as I've done this show and talked more and more with various authors on subjects and topics, that it's. Oh, it's a learning field to look at something like this and change your shift in perspective about how AI can augment what you do and take you to new heights, take you to new levels.

[20:39.8]

So you have this philosophy where philosophy meets technology, and you weave together thinkers like ancient Greece and postmodern philosophers, Prometheus and so on. And one particular striking concept is what you call the Promethean lag.

[20:59.6]

Yes. Okay. So is it Gunter? Andres? Is that how you say the name? Gunther? Gunter? Well, that's German. It's German. I don't speak much German, but I did. The idea is that we can't keep pace with what we've created.

[21:16.2]

So in the age of Chatgpt and Claude and everybody else and Gemini and whatever and generative AI, how has this lag become more pronounced than Anders could have imagined. Great question.

[21:33.8]

Just one remark. This philosopher comes from my city. So it was very interesting to discover that he actually lived where I live now. How many years ago of almost a hundred. Wow. It was, at that point, German city, though it's Polish city.

[21:52.4]

But we come from the same claims. And there are some other philosophers from my city in the book. But just to answer your question, the Promethean lag is an important concept for us because think of how we use large language models and let's focus on ChatGPT for a moment.

[22:08.6]

We don't try to understand how they work. We go with the flow. Right. We just, oh, it gives me the answers that I need. Okay, so let's use them. And then we discover some things might be made up next. Messed up, Right?

[22:25.3]

And to me, the Promethean lag is a concept that he wrote in the book in the 60s called the Obsolescence of men. Was pre digital era, Right? Yeah. And he already thought of that, what we're facing currently, the obsolescence of men. And he thought of technology as something that should empower people.

[22:46.5]

Okay. That we should learn how to use, like today. ChatGPT, maybe we should ask ourselves questions. What is it good for? How we should actually leverage that marvelous technology. Because it's not. I'm not criticizing it.

[23:02.3]

I'm just asking to consider how this thing really works before we start using it or during the usage of it, ask ourselves deeper questions, and by that, discover how we may leverage it. The Promethean lag measures, you know, our competence, where it should be and where we are.

[23:22.1]

I think there's a lag. We're lagging behind. The technology companies create something that we simply yet cannot comprehend how it works. And until the point we do, we're at risk of misusing it. Understood.

[23:38.3]

And I would agree. On the other hand, we have to use it to figure out how it works. Yeah. So it's like you dive into the pool and swim, or do you just put your toe in and, you know, and then take your toe back out because you have fear.

[23:55.8]

And I don't think we need to be fearful. Although I have talked to many people that are fearful of it. You know, so you discuss the shift from soulness to thingness. Okay. Quoting Martin Luther King, diagnosed that modern man has allowed his spiritual discipline to lag behind his scientific and technological development.

[24:24.8]

Pretty interesting statement coming from Martin Luther King. As someone deeply embedded in AI transformation, which you are, how do you personally navigate this tension, this tension between the spiritual discipline and what he was talking about, how the man needs to look at that and navigate that.

[24:49.1]

And how do you prevent yourself from becoming a thing in service of the system? Okay. You know, I'm blessed, by coming from a different culture, Central European culture.

[25:04.6]

And I discovered while writing this book that there's a crack between Western philosophy about abstraction, about thingness. Right. About becoming more and more abstract and Central European philosophy. And Central Europeans seems to be very, for them seems to be very, stubborn in terms of keeping the humanity intact when using technology.

[25:33.1]

And the Western philosophers, they just went with the flow of getting more and more abstract, objectifying things as they went. And to me that gives me a grounding to speak about the process of losing your humanity as you go.

[25:54.7]

Because some of the things we cannot really, from our Central European perspective, understand why they are so easily sold as, you know, products, services. So for example, technology.

[26:11.4]

Any piece of technology that pretends to. That can become your friend. Right. I don't buy it. This is. I call it a bluff. I don't believe that any large language model can really become your friend. And it.

[26:26.8]

Maybe it shouldn't be. From my perspective, maybe we should, push back on this. Right. Or you mentioned that I have exposure because I co founded and lead AI Implementation company.

[26:42.4]

So we do ar, but we don't think of it as, a like fully human companion. I think of it more as a very useful interface. Much better than the classical buttons or, you know, menus, what have you.

[26:59.5]

So it's kind of a tool to get something done. If you want to check your flight using Chatbot, you want it to be, you know, not your friend, but. But useful one, formative. That's a tool. So that's the difference between those two things.

[27:15.3]

And as long as we take the technology in and start to think ourselves as a piece of technology, we kind of lose distinction between us as humans and technology as it is.

[27:32.9]

And to me the distinction being socially European is very, very important. And I write about this in the book. Like I'll give you one example from me. Early on in the 40s, the technology was called cybernetics. Okay. Do you remember the Cyberdeen from Terminator 2?

[27:51.3]

They're a company that created those robots as cyborgs. It was because the concept. Exactly. The concept came from the word cybernetics. It was drastically different thing when Central Europeans thought of cyber cybernetics.

[28:10.8]

And let's say Western and American. Western Europeans and Americans. For us, cybernetics was a way to, to provide the ruling with support of the system, of the nation, so people flourish.

[28:30.2]

Okay. So it was about people and getting them to some better state. For Americans during the war, what happened? And that's that cybernetics was a kind of like a sticker to put on machines, on machines of military use.

[28:47.4]

So there's a crack. You don't think of a human when you're fighting with enemy planes. Right, right. You just need to destroy that object. And in Central Europe, we were thinking about governing nations, improving lives. And I think the distinction is quite important because now we're at the point that we're losing our humanity, and we perhaps could draw something from the Central European thinking to rebalance things a bit when we think of technology.

[29:16.1]

You know, you bring up an interesting point about how people in the EU looked at it differently in the US did in the 60s. And I think that, our cultures, you know, the differentiations in cultures, just like there are differences in cultures in the businesses that you go in and you work in as to whether or not that group of people will embrace it or shun it.

[29:46.3]

Right, right. And I think that, we're all in a position now. Meaning when I say all, I, would say a majority of us, are learning to adapt to it. And I think it's an adaptation as a human being, not a human doing.

[30:08.5]

To really figure out how to do it. Now, you're currently consulting with major EU and US companies on AI transformation, while simultaneously warning about technology's, dehumanizing effects.

[30:26.3]

How do you reconcile these two roles? And what does responsible AI adoption look like in practice? Just to make it clear, I'm a tech entrepreneur.

[30:41.7]

I love technology, I breathe technology. But I. With the book I'm trying to invite, to think deeper about the concepts that, are related to technology. Think of it as a, way to expand the vocabulary.

[30:57.6]

We have the important topic to discuss, but we're lacking words. Well, what I was trying to do, and we're creating this book, is to expand that vocabulary so we can have a meaningful conversation. To me, currently, we're converging to some point of view.

[31:14.2]

I don't want to call out from where that point of view comes out, but we're basically, scared of losing quite a bit in our lives, our jobs, our futures. Right. So we're converging to some point where we are at, fear.

[31:30.7]

And I don't think we should be. I Think we should leverage the magnificent technology by seeing through how it really works, educating ourselves and getting a better perspective. But the way to do that is to.

[31:46.1]

By expanding vocabulary of words that we use to. When we speak about, let's say, our own humanity too, right? Think of the concept like soul. This is kind of obsolete when you think of it now. It's like nobody really cares, right?

[32:03.2]

And that's why I invited some poets into the book, right? I invited like, for example, a French poet who defined the term modernity. I play with this concept because it was, you know, refurbished so many times in the past just to provide some new perspectives.

[32:19.2]

And now to the point. So what is techno feudalism? I mean, you know, you mentioned it here and you, you discuss it, your discussion, and I hopefully I don't butcher this name, but it's op Edal trap. How do you say it?

[32:35.0]

Odipus trap. Oedipus trap. And then you say techno feudalism. And then you say that this form of digital serfdom, right? And that when we're in the boardroom helping executives implement AI systems, how would you, meaning bart, ensure that we're not building the very, prison that you're warning us about in the book?

[33:05.7]

That's not something we do in our work, you see, and I see it in every project. I'll give you an example. Every time when we approach, teams that are going to work with us on AI implementation, people are scared that they're going to lose their job.

[33:23.1]

But what happens, what really happens at the end of some phase when we prepare them to understand what we are actually going to do, they appreciate the work because the mundane work is gone right away or reduced, right? And they say these were the things we never wanted to do, right?

[33:41.3]

And it's better that some AI component of a process now handles that for us. And that's my thing about it, is that it can bring the best of people. If AI is applied well, it can bring the best of people. Look in the book, in the chapter one, I have a story about Frederick, Taylor who said that the system should come first.

[34:06.2]

And it sounds like wrong, right? Okay, so what's the place of the people and if the system come first? But what he really meant, and I write about it in the book, is that, we need best people. We need to put the system first so people can improve and do what they can do best, you see?

[34:28.6]

So to me, applying technology is a way for our humanity to flourish. And I understand that this is not Something that you hear in the mainstream media these days. But maybe we should think about human flourishing supported by the systems.

[34:45.8]

Well, I think as a deep thinker that you are, fundamentally, if you look at, the eras that we've gone through now, you could call this the digital era, information age, the agricultural age, all of these eras that we've gone through for the years and centuries in history.

[35:08.5]

I think some of that fundamental hard work gave people opportunities to think. In other words, working physically, which we don't do much of anymore as a society here in the US and in many parts of the world.

[35:27.4]

It was a place for us to lose our mind and gain our mind. It was a way for us to think through how to do something differently that might help us. Do you really believe if this technology can give us more time, we will use that time fundamentally to better ourselves?

[35:49.2]

Or do you think we'll just get lazy and fat? It really depends on us. Right. I can tell you from my perspective, the time that I gain. I, used to educate myself, I used to write books, I used to do sports.

[36:04.4]

Right. So I appreciate every moment of it. And for others, it might be, just the way to spend more time to watch streaming. I cannot help for them, but I would love people to be in a position to decide.

[36:20.3]

Right. And the more we would choose the first route, the better. Agreed, Agreed. Only time will tell for that to work itself out and to see how much elevated in consciousness and education and intellect, people will become as a result of their free time.

[36:47.1]

I know for me, it's been endless years with heads in books and interviewing authors, and it's what I love doing. Right, exactly. And it is a way for me to expose people to ideas and concepts that they may not get exposed to other likes.

[37:05.6]

Like what we're doing right here today with this. Now, you mentioned that AI armoring and the reversal of the thinks challenge, where we become the ones being tested rather than the questioners.

[37:21.3]

So in a world where algorithms increasingly determine our credit worthiness or job opportunities or social connections, what does it mean to reverse this challenge and reclaim our agency?

[37:37.6]

Look, we don't have to accept this deal that is presented to us. Do you have a good example comes with music that we started with Spotify, where you're getting lost in the cloud. It's good to explore music, discover new music, but is it really good, something that you want to use at all times?

[37:59.3]

For example, I'm using a mix of that. I use Spotify to explore music, but the things that I like, I really buy as a record. If I cannot buy it, I use mini disc technology to capture it. Like cassettes.

[38:14.9]

In the past days. What I love about using, mini discs, a physical media, is that no one can tell what I'm listening at the moment. Just think of the beauty and the simplicity of this. No one's tracking you. No one is tracking me.

[38:31.9]

So that's what I mean is that we cannot, we don't have to accept the deal that is presented to us and be exposed at all times. So they capture all the data and they just use it. They use it to advertise back to us to buy more of something we don't use.

[38:51.7]

In reality, in my reality, I mean, it is, to a big extent, changes buying patterns, changes patterns in our life, changes how we interact with people. All of these things have been, a big challenge in our society, especially.

[39:09.0]

I don't know how it is in Europe, but it is here when the kids come to go out to a meal with somebody at a dinner and they're all on their iPads and no one's looking at one another or talking or speaking, over the meal. I mean, that's a very simple example, but it's a very real example of our connectivity, of the fact that, recently reported, loneliness, and loneliness amongst younger people is at a severe, severe level because this technology has captured them, it's encased them, it's embodied them in a sense that they're one with it and they haven't found a way to break free from it.

[39:49.9]

And not that we're going to give them a solution here today on this podcast, but the reality is that to me, is a challenge of building compassion in the world to actually help solve problems. Works, you know, with these kids.

[40:08.0]

What I think is happening is that they are presented with fake experiences. Like, I like video games. I sometimes play video games, but I don't spend all my time playing video games because it would just shrink the world that I live in. And technology maybe is going from the opposite direction, as it should, to create fake experiences, to create conveniences.

[40:29.7]

To me, for example, the convenience of moving around. I use motorcycle at all times. And we do have seasons where I live, right? But even right in the winter. Why? Because it's a kind of experience, right? I know how to do it so I'm safe. But it's an experience.

[40:45.5]

It's not just getting from a point A to point B. So maybe we're getting the technology wrong. And I write about this in the book instead of looking to be more convenient and having exposure to some fake experiences, but maybe we should look for those real experiences in the world supported by and enhanced by technology, you see?

[41:06.4]

So it's just like I'm trying to flip this paradigm a little bit. So let me ask you this. You know, you lecture postgraduate students on entrepreneurship. Yes. And management. This age of AI, what's the one thing you wish that they understood that they consistently don't?

[41:26.0]

And what blind spots do you see that this next generation in approaching this technology? Yeah, that's great question. I think the over reliance on technology without knowing how it works, it really hurts everyone.

[41:42.0]

Not only my students, but like everyone. And as you mentioned, early on I, was the hacker, right? And what hacker does, he really tries to understand how the system works in order to hack it. You cannot hack something that you don't know how it works, right?

[41:58.0]

So to me, this mindset, it's really important to learn what you're using as a tool, what you're dealing with, let's say as a system. And that's the first thing that I want people to do to be curious how this thing work when they are using it.

[42:16.8]

Because otherwise you're just exposed to, very negative outcomes of using something that we actually don't fully understand. So you address that. And I think that as long as they fully understand the potential consequences or outcomes, we're in good shape.

[42:39.7]

And I'm glad that you are lecturing because given the content of this book. Book, this is exactly what they need to hear. Now look, your book ends with the epilogue titled the Riddle that Doesn't Exist. Yes, that's tantalizing, obviously.

[42:57.9]

Without giving too much away, can you hint, at what you mean? And is the suggestion that you've, been asked the wrong question all along or that the answer was like as you said, with the Sphinx was within us the whole time?

[43:19.9]

I think without giving too much, I think when, you know, being in the situation, being challenged, I think we should come up with our genuine answers by ourselves. Because the process of arriving at answers, gives us meaning.

[43:39.6]

If we take the answers that are already made by something, it's just passing information, but it does not create meaning. The pursuit to find the answers to difficult questions, like who we are, is something that we really need to discover.

[43:58.3]

So without giving too much, I would say there's a challenge. Yes, you can think of it as a riddle, but it's up to us how we approach it either we try to approach it with ready made ones and face the prospect of the same fate as ODQs, it really destroyed it.

[44:17.6]

Or we can be more mindful in our pursuits and force ourselves to arrive at those answers and gain meaning in the process. And I think the key is, and to underline gaining meaning in the process.

[44:33.1]

And that's again with us all using AI. Gaining meaning in the process. Right. As you said, hopefully we're going to take that time and we're going to elevate our education, our understanding, those kind of things, that we're going to be inquisitive, that we're going to be more curious, that we're going to want to understand things versus just taking it for granted.

[44:57.3]

And I think many people listening, me included, we don't understand how AI works. We don't have a clue. We're not computer scientists like you are. We do understand that the tool is assisting us.

[45:12.8]

It's giving us more time to do other things that we would rather do, which is great. So with that, let me go to this closing question because this is a wonderful book. Everybody again go out and get a copy and look to the link below here to Amazon to get your copy.

[45:32.7]

And also you can go to the website by the same name, Resort by progress. That's right. So I'd encourage you to go do that. So you mentioned that in your bio that you're already working on your next book about the hidden dimension of life's treasures or on the outskirts of the online world.

[45:52.8]

After spending years investigating how technology has riddled our progress, what have you discovered about what lies beyond the screen? And what treasures are we potentially missing?

[46:10.9]

What I see. Let me answer your question this way. What I see is that there's less and less important things online. Think about it. There's this concept of Internet becoming increasingly dead because there are bots chatting with each other over Reddit instead of real people.

[46:28.5]

Right. So there's less real genuine exchange instead of just marketing as with Hegel. So my point was that, okay, maybe there's something leaking out. And where does this go? What I see is that there's this important dimension that we forget these days.

[46:51.0]

And it's a dimension of yourself. It's a dimension that happens, a world that happens within you. And that's what I'm going to focus on. You see that we had a Chopin competition in Poland, a, week back.

[47:07.7]

And what I realized is that there are artists coming to the stage Performing some Chopin piece. And when you look at them, they look nothing, right? Like the ordinary people. But when they start to play, they open up their world and, you know, you can play, you know, the correct, order of the notes, and that's gonna be good enough.

[47:30.2]

But they go way beyond that. They have a certain way of expression, impression that you can tell that there's. It's emotional, it's personal, and it's a window into the world. So what I'm trying to do is to look.

[47:45.6]

Open those windows up, right, and look into the worlds that don't are not available online. Because I think people of substance, There's a lot of examples out there, withdraw from online world for various reasons. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

[48:01.6]

And when they do that, I just want to interview a lot of them and create a story about the things that we perhaps cannot find online. Maybe we should look somewhere else. And, when we find them, maybe we should ask ourselves what's within our world, too, and build it up.

[48:20.9]

Well, you know, many of those people, like you said, have made, a lot of money and have withdrawn from the digital world. I think Richard Branson would be one of them. He's probably a pretty good example. And I think what he's found is, obviously that nature is more important than the digital world to him.

[48:41.7]

And many people who do withdraw find that the natural world. I was expressing to you, I think, when we talked the other day and I played for you, Jane Goodall's, a goodbye message. And, you know, the.

[48:59.0]

The interesting thing is, is that we have to have stay positive, have hope, understand that this technology can change the evolution of our world. Kind of a dark world. We're losing species like crazy.

[49:15.7]

We've got global warming going on. We have plenty of problems to solve. And I really believe that AI can help to solve many of these problems that sit right in front of us and are staring us right in front of. Absolutely. And I just did a podcast with Michael Johnson, the producer of a new video, around our soils, Right.

[49:39.0]

And it was an amazing podcast where Wes Jackson, a very deep thinker, has created an institute, the Land Institute, that literally is looking at how these soils are degrading. And the theory right now is there's only about, 60 harvests left, right?

[49:59.6]

So it's a short period of time, maybe 20 years or less. So we've got to do something. AI can be some of the tools that we use to help us. And I'm encouraged by it, Bart, and I'm encouraged by your book but there's a risk. There's a risk in it because I.

[50:16.3]

I even show a few cases in the book where the technologies of the past were first harmful because before they did, they become useful. And I give an example of first commercial train line opened in Ukraine, 1800s.

[50:32.2]

Can you imagine a train approaching station killed people because they were surprised with the speed of this thing moving in. Right. They were just taken by surprise. And that's perhaps a good illustration of what we're facing here with AI. I don't want this thing to, you know, wreak havoc.

[50:51.6]

I want this thing to be kind of understood so we can step back, let this train enter the station right before we say, and then enjoy the ride. Well, I think the listeners have enough of a flavor of this book, to really.

[51:09.4]

It will allow them to think deeply. It will allow them to get a new perspective about how they're looking at their world in general, not just AI, but literally at a deep level, deep philosophical level.

[51:24.8]

And, bart, I want to thank you for being on Inside Personal Growth and sharing a little bit about your personal story and a lot about the Sphinx and the riddle, by progress. And thanks so much. I really appreciate you. I appreciate everything that you do. And, I know my listeners are going to enjoy this podcast.

[51:43.4]

Thank you. If this book helps at least one more person, then I'll be super happy about that. So thank you for having me here. It was a really pleasure to have this conversation. Yeah, I enjoyed it very much. Thanks. Namaste to you.

[51:58.7]

Thank you. Thank you for listening to this podcast on Inside Personal Growth. We appreciate your support. And for more information about new podcasts, please go to inside personal growth.com or any of your favorite channels to listen to our podcast.

[52:15.2]

Thanks again and have a wonderful day.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply